newspapers, catlogue, drake university, 2004

newspapers, durban art gallery, 2009

newspapers (dispatch), st. louis, 2004

manufacturing consent, film stills, 1992

newspapers, durban art gallery, 2009

newspapers (world cup), richmond, 2010

post/times, detail, washington post, 2002

newspaper research, durban art gallery, 2009

washington times, in process, 2002

post/times, fusebox, 2002

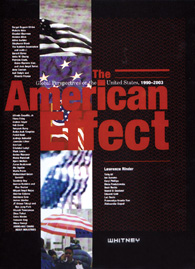

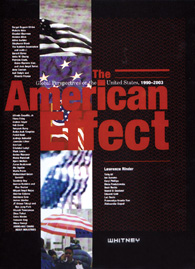

the american effect, whitney museum, 2003

post/times, detail, washington times , 2002

|

NEWSPAPERS, 2001 - 2004

THE IMAGE OF SOUTH AFRICA

Siemon Allen

In 1992 I saw the film Manufacturing Consent* at the annual film festival in Durban, South Africa. It was a three-hour documentary on the life and work of the linguist and political activist Noam Chomsky. In order to show some filmic equivalent of concepts described by Chomsky in his writings, the filmmakers had produced a number of effective visual analogies. One particularly memorable example addressed The New York Times’s quantitatively unequal coverage of the concurrent political situations in Cambodia and Timor. Two narrow rolls of paper were shown placed side by side. Both had been constructed by placing the column inches of articles from The New York Times archives end to end. The roll representing coverage of the situation in Timor traveled only a couple of feet, while the other, covering the war in Cambodia, stretched the length of a football field. The short scene dramatically illustrated how news coverage in the United States had defined what was of importance in distant regions of the world, and it communicated this in a manner that was concise and clearly readable. It struck me at the time that 1975 to 1979, Chomsky’s research period for these articles, were the same years that brought to South Africa the Soweto uprisings, heightened police oppression, the expansion of separate development, and the death of many activists, including Steve Biko. At the time I wondered what an equivalent roll of South African articles would have looked like.

Later, I asked myself how the presentation of articles dealing with South Africa from any given U.S. periodical might operate if organized indexically in a way similar to those shown so graphically in the film. What might this presentation say about South Africa, and, reciprocally, what would it reveal about the extent and nature of U.S. media coverage of South Africa? How is the South African image projected, interpreted, and received? What is represented or misrepresented? What exactly is the image of South Africa?

As a South African artist living and working in the United States, I have been particularly interested in the dynamics of how a country is imaged and how it in turn participates in a kind of imaging of itself. This notion of the importance of imaging became even more significant when I came across a speech by South Africa’s minister of environmental affairs and tourism, Valli Moosa, on a government website. His office made a highly published call for a positive “branding” of South Africa internationally and included the recruiting of “non-government South Africans living overseas” to act as “ambassadors” for the country. I was at that time beginning a project that later developed into the exhibition Stamp Collection (2001), and for me, this direct (and official) articulation of the need to “brand” South Africa echoed the ways in which an image on a stamp also operated in the construction of a national identity.

In light of Moosa’s declarations, the presentation of a complete collection of South African stamps in the United States seemed particularly significant. With Stamp Collection I sought to explore the political history and shifting identity of South Africa through the collection, cataloging, research, and display of postal stamps released in the country. I intended to look at how the country, over time, had chosen to represent itself both within its borders and internationally. The stamps were sorted and configured chronologically, and I produced an accompanying guidebook that operated as a kind of subtext of concurrent and often contradictory historical events.

I was aware of the fact that in spite of what I observed as an intense interest in the phenomenon of the New South Africa, it was a place that seemed to be accessible only through a small number of familiar media images. I wondered if the stamps might provide a record of how radical had been the change in voices that sought to define South Africa. I also wondered if I might discover for myself and somehow present in the work lesser-known events or aspects of South African culture and history. Admittedly, the final narrative was a fragmented one. It spoke not only through what was shown but also through what was not, and so a careful look at the artifacts required one to bring to the task a certain degree of criticality. Given that the stamps presented an official history, much of what was revealed was unintentional, and much was concealed as well.

In this light I saw the presentation of the Stamp Collection, particularly in Washington, DC, as both a subtle critique and a kind of covert participation with the minister of tourism’s stated agenda. Stamp Collection was first shown at the Corcoran Gallery, just one block from the White House. The exhibition design mimicked a historic museum display. I presented the stamps with the admission that they are carriers of images that most often mask or remain silent on much that is officially unacknowledged. Yet I was compelled to devote such care to the arrangement and display of the precious artifacts, and I approached the conveyance of the historic information with such detachment, that I wondered if the exhibition did not ultimately operate with a kind of feigned complicity in the dissemination of the stamps’ propagandistic messages.

Newspapers, like Stamp Collection, developed out of what I regarded as a continued investigation into this idea of imaging South Africa, but in a way that also looked at the news media. Like Stamp Collection, Newspapers is an ongoing collection, realized through the gathering of cast-off ordinary items. As was true for the stamps, the individual newspapers are of questionable value once they have been used. In the case of the newspaper, its currency is spent when the information that it carries has been transmitted.

The newspaper project differs, however, in that it has been the most methodical of all the collection projects. My collecting of U.S. papers began during the coverage of the UN Conference on Racism in Durban (my hometown) in late August 2001. I initially bought various papers in an attempt to follow whatever coverage there was of the conference. But with the events of September 11, which occurred a couple of days after the closing of the conference, I was compelled to continue. From that time I collected, on schedule, daily newspapers (looking for articles on South Africa) from a number of selected U.S. cities: Washington, DC, New York, Los Angeles, Boston, Baltimore, and Richmond. I was interested in how the media produced in each place would reflect how each of those communities constructed (or received a construction of) an image of another place—in this case, South Africa. Given that the collection displayed was the result of a very methodical daily action of buying and cataloging, it was as if a common routine had been made self-conscious. The newspapers were for me operating as a complex carrier of information, a diary, and a potential future archive. As the project developed, the reach of my collection expanded to include newspapers from the cities where the project was scheduled to be presented: St. Louis, Houston, and Des Moines.

It seemed significant that the collections began with the Durban Racism Conference, a controversial event in which the United States did not fully participate. When the events of September 11 then occur, they do so within a chronology that has already been set in place. The events of that day and their aftermath have continued as the dominant narrative in the U.S. media, but in the collection they are actually part of a different story. It is as if the collection is about an attempt (and the impossibility of such an attempt) to shift the gravitational pull to a different center—from the perspective of the United States to that of South Africa. For me, the collection represents a type of counter-narrative, and perhaps, in some sense, it could be interpreted as a kind of counter-nationalism.

South Africa is a place that I have experienced, albeit in a very limited and personal way. It has an image that I have constructed and reconstructed through memory, which is now presented back to me through the filter of the U.S. news media.

Stamp Collection presented an image of South Africa that was and is constructed by the official voice of the government and was therefore, for me, an internal construction of image. Such a collection is a kind of autobiography of a nation and says much about how the country perceives itself, or, even more important, about how it seeks to construct an identity for itself. Newspapers presents another image of South Africa, but one that is constructed externally.

This external media image presented in the newspapers, unlike the internal image constructed by the South African government in the stamps, is not only manufactured in the United States but also exhibited there. With Stamp Collection, I had asked myself whether I was complicit with or critical of the South African government’s propaganda. In terms of the newspaper project, I now ask myself: If the newspaper images displayed in my work are constructed by the U.S. media for a U.S. audience, by re-presenting these images, do I not then perpetuate notions of the country that may be stereotypical or limited? Conversely, I also wonder if, by presenting these images, I might allow the audience to refocus on important issues from South Africa that they might have overlooked; on any given day’s news coverage.

For me, the work addresses the profound implications behind the simple act

of reading the newspaper. It is about the everyday experience of “the world in your living room,” or, as Walter Lippmann has said, “the world outside and the pictures in our heads.”

from the publication Newspapers edited by Cira Pascual Marquina

published by Anderson Gallery, Drake University, 2004

ISBN 0-9749296-1-1

Library of Congress Control Number: 2003117090

* Manufacturing Consent: Noam Chomsky and the Media (film stills), 1992, directed by Mark Achbar and Peter Wintonick, Necessary Illusions Productions, National Film Board of Canada Co-Productions, Zeitgeist Films

* Walter Lippmann, "Public Opinion", Macmillan, NY, 1922

|

newspapers (register), the des moines register, anderson gallery, drake university, 2004

The Des Moines Register version of Newspapers at Anderson Gallery, Drake University featured not only the grid presentation format but also an alternative view. This new version consited of the South African articles from The Des Moines Register, The Washington Post and The St. Louis Post-Dispatch, cut and laid end to end in three comparative, linear lines. A reference to the comparative device used in the Chomsky film, Manufacturing Consent (1992).

newspapers (strips), anderson gallery, 2004

newspapers (strips), anderson gallery, 2004

newspapers (register), the des moines register, anderson gallery, drake university, 2004

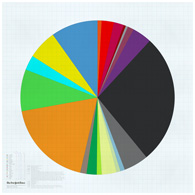

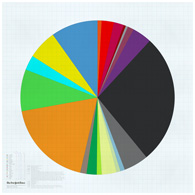

article and image analysis, 2004

The catalogue for the Drake University show also featured an 'article and image' analysis of the various newspapers for the collection period. These included The Washington Post, The Washington Times, The Des Moines Register and The St. Louis Times-Dispatch.

newspapers (register), the des moines register, anderson gallery, drake university, 2004

newspapers (register), the des moines register, anderson gallery, drake university, 2004

newspapers (dispatch), st. louis post-dispatch,

a fiction of authenticity, cam st. louis, 2004

|

INTRODUCTION: NEWSPAPERS IN PROGRESS

by Cira Pascual Marquina

The media as the medium. The medium is the message. These two propositions—the second from Marshall McLuhan—define the principal axes on which South African artist Siemon Allen (born 1971, Durban, South Africa) articulates his archivally-driven yet self-reflexive practice.1 On the one hand, the work functions as a content-driven representation, examining the way South Africa is imaged in the media (here, for South Africa, one may substitute another global issue, such as the Iraq war; while “media” must be construed broadly to include such elements of visual culture as comic books and postage stamps); these documents are often subjected to a spin comparable to a Situationist détournement, that is, a turning aside from their normal purpose.2 On the other hand, Allen’s work deliberately nods to the relative autonomy of late Modernist art, including many of its formal means, such as the all-over composition and the monochrome.

Factual or documentary work, though it is rarely media-focused, is a principal tendency in South African contemporary art. There, the archive, because of its evidentiary value, has for obvious political reasons acquired a central position in art practices that aspire to social critique. Archives made of ID cards (Sue Williamson); declassified documents of the apartheid regime (Kendell Geers); scavenged materials such as maps, ethnographic photographs, and newspaper clippings (Moshekwa Langa); and kitschy curios and memorabilia (Penny Siopis) form a vital part of the grammar of South African art practices. In this work, the valorization of “truth”—perhaps surprising in contemporary art because it hints at essentialism—reflects a corrective to the historical legacy of overt deception, comparable to the work of the post-apartheid Truth and Reconciliation Commission.3

Both projects shown at the Anderson Gallery participate in this archival discourse and form part of Allen’s ongoing Newspapers series, initiated in 2001, when the artist began systematically collecting coverage of South Africa in The New York Times, The Washington Post, and The Washington Times during the UN Racism Conference in Durban. (He eventually expanded the range of his collection to include The Baltimore Sun, The Boston Globe, The Des Moines Register, The Los Angeles Times, and The St. Louis Post-Dispatch.) The first project, entitled Newspapers (Strips), is made of three lines of newspaper clippings, each drawn from a single source—The Des Moines Register, The St. Louis Post-Dispatch, or The Washington Post—which form horizontal strips down the gallery wall. The work is inspired by a sequence from Mark Achbar and Peter Wintonick’s 1992 film Manufacturing Consent: Noam Chomsky and the Media, in which a comparison is made between column inches of The New York Times documenting Cambodia’s Khmer Rouge genocide and those devoted to concurrent massacres in Timor.4 We are shown, through this simple visualization, that

the Times’s attention to the Khmer Rouge regime was ongoing and deep, whereas the Timorean genocide was hardly a blip on that newspaper’s radar (certainly a reflection of the Times’s editorial self-alignment with the United States government’s ideological battle against communism as well as its quietism regarding human rights violations that coincide with corporate and governmental interests).

In a second work presented at the Anderson Gallery, Allen covers pages of The Des Moines Register with tracing paper and clips windows through it to bring to

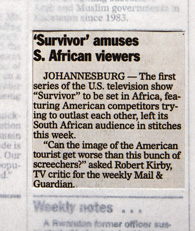

the forefront stories dealing with South Africa. In this work, referred to as Newspapers (Register), the quantitative comparison of newspaper coverage turns into a more open-ended commentary on its quality. This version of Newspapers (152 selections collected between November 2002 and January 2004) reveals a bleak picture of The Des Moines Register’s coverage of events in the southern tip of the African continent. The journalism is clumsy, while its ideological color is often blatant. For example, Nelson Mandela’s annual Christmas party for children is “spun” by a negative story focusing on a fight that broke out during the celebration. The content of the coverage (with

an appalling lack of attention to the AIDS crisis and a bizarre focus on golf stories) is curious, to say the least. It is bitterly humorous that golfer Ernie Els appears as often as Mandela and four times as often as President Thabo Mbeki.

The heterogeneous and unforeseeable character of much of the material in Newspapers (Register) points to an important feature of Allen’s work. In both Anderson Gallery pieces, the promise of revelation, which forms the interpretive horizon of most archival and documentary work—as well as the rationality and even instrumentality that attends that promise—operates in counterpoint with a serial aesthetics that puts system before sense. The implicit distancing effect of this systematizing trope calls to mind the liberatory potential that, from the Surrealists to Pollock, has been vested in techniques of automation. Despite this shared lineage, Allen charts a manifestly different course than that found in the “automatic” postindustrial and diagrammatic work of such artists as Franz Ackerman, Julie Mehretu, and Matthew Ritchie. In Allen’s work, two features that are central to the project of conceptualism—a drive to function as a transparent vehicle for the artist’s content together with a rigorous method that obeys its own internal system—are held in fine balance. The result is work that presents concrete and content-driven depictions of issues while not failing, along the way, to keep the rhetoric of depiction an issue.

Cira Pascual Marquina, former director of the Anderson Gallery, Drake University, is an independent curator based in Baltimore, MD.

1. Marshall McLuhan, Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man (New York: McGraw-Hill Book

Company, 1964), p. 7.

2. “Détournement of pre-existing aesthetic elements. The integration of past or present artistic production into a superior construction of a milieu. In this sense there can be no Situationist painting or music, but only a Situationist use of these means.” From “ Définitions,” Internationale Situationiste, 1 (June 1958), pp. 45–46.

3. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), in operation from April 1996 through June 1999, was established by South Africa’s Government of National Unity to investigate apartheid-era atrocities and human rights abuses. The TRC’s mandate was to grant amnesty to those who confessed their roles in full and could prove that their actions served a political objective. The goal of the TRC was to bring closure and to prevent more cycles of racial and ethnic strife. Further information about the TRC is available at www.gov.za/reports/2003/trc and www.truth.org.za.

4. Mark Achbar and Peter Wintonick, directors, Manufacturing Consent: Noam Chomsky and the Media, 1992. Necessary Illusions Productions/National Film Board of Canada Co-Productions, Zeitgeist Films.

from the publication Newspapers edited by Cira Pascual Marquina

published by Anderson Gallery, Drake University, 2004

ISBN 0-9749296-1-1

Library of Congress Control Number: 2003117090

|

peffer, streitmatter, powell, panel discussion

allen, kirkman, panel discussion, 2002

panel discussion audience, 2002

gopnik, panel discussion audience, 2002

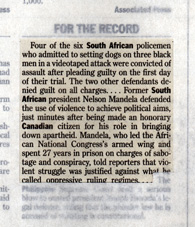

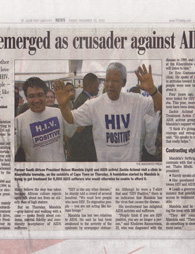

the weekly mail, june 20-26, 1986

In the 1980s South African newspapers had to present each days issue to a government censorship board for approval prior to publication. In an act of defiance, Johannesburg paper, The Weekly Mail, made the editorial descision to print the paper with the government's censor bars. John Peffer presented this slide in the panel discussion.

post/times , detail, washington times, 2003

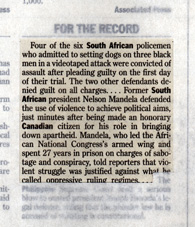

Mark Shuttlework, a South African businessman paid $20,000,000 to be the world's second space tourist. This article was featured on the front page of the Washington Times. (April 26, 2002)

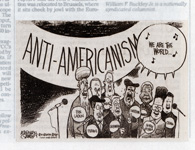

post/times, detail, washington times, 2003

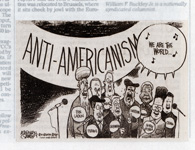

This cartoon from the conservative Washington Times features a number of critics and enemies of the United States in the wake of the build-up to the Iraq war. Nelson Mandela is pictured alongside Osama bin Laden and Kim Jong Ill. (Febrauary 19, 2003)

post/times, detail, washington times, 2002

post/times, detail, washington times, 2002

post/times, washington post, fusebox, 2002

post/times, washington times, fusebox, 2002

In the Post/Times exhibition at Fusebox, theWashington Post and the Washington Times were set up on opposing walls in a kind of face-off. These are the so-called left and right leaning papers in Washington. For the show, The American Effect, at the Whitney Museum in New York, this piece was truncated but shown in a similar face-off way.

newspapers (dispatch), st. louis post-dispatch,

a fiction of authenticity, cam st. louis, 2004

newspapers (dispatch), st. louis post-dispatch,

a fiction of authenticity, cam st. louis, 2004

newspapers (register), the des moines register, anderson gallery, drake university, 2004

post/times, detail, washington times, 2002

post/times, detail, washington post, 2002

In my 'article and image' analysis for the research period (2002/2003), I found that the golfer, Ernie Els, was the number one imaged South African in all the US papers that I collected. Coming in second in the research was Nelson Mandela and then Thabo Mbeki.

post/times, detail, washington times, 2002

post/times, detail, washington post , 2002

post/times, detail, washington post , 2003

newspapers (dispatch), st. louis post-dispatch,

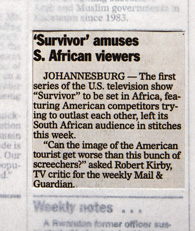

a fiction of authenticity, cam st. louis, 2004

In a touch of cyclical irony, articles about the project itself began to be included in the later presentations of the travelling show.

newspapers (dispatch), st. louis post-dispatch, newspapers (dispatch), st. louis post-dispatch,

a fiction of authenticity, cam st. louis, 2004

post/times, washington post, fusebox, 2003

newspapers (dispatch), st. louis post-dispatch,

a fiction of authenticity, cam st. louis, 2004

walter lippmann, public opinion, 1922

|

POST/TIMES - MEDIA COVERAGE OF SOUTH AFRICA AND THE WORLD

Panel Discussion, 2002

Rodger Streitmatter

Adam Clayton Powel III

John Peffer

Larry Kirkman

The following is an edited transcript from a panel discussion held on September 30, 2002, at FUSEBOX in Washington, DC. The discussion took place in conjunction with Siemon Allen’s exhibition Newspapers, which featured The Washington Post and The Washington Times. The panel was sponsored by FUSEBOX and the American University School of Communication.

The panelists included: Rodger Streitmatter, Professor of Journalism at the American University School of Communication; Adam Clayton Powell III, General Manager of WHUT-TV at Howard University and former Vice President for Technology and Programs at the Freedom Forum; and John Peffer, Visiting Assistant Professor of African Art History at Northwestern University.

Others who took part in the discussion included Larry Kirkman, Dean of the American University School of Communication, who also introduced the event; Sarah Finlay, Director of FUSEBOX; Blake Gopnik, Art Critic for The Washington Post; Siemon Allen, the exhibiting artist; and various other members of the audience.

John Peffer: I thought it would be interesting in the context of this show to ask first why we should bother considering art and news representations in the same space at the same time. Perhaps one key is to be found in the name of an Afrikaans newspaper in Johannesburg called Beeld. If you look at a dictionary translation of “beeld,” what you get is “image, likeness, representation, picture, painting, statue, sculpture.” It is interesting that in Johannesburg it is the name of a mainstream newspaper. If you think about the word English word “representation,” there is also a kind of double or triple meaning. This is particularly relevant if you wish to think of artists as representing the world or representing a possible vision of the world. We also talk about politicians representing their constituents. We talk about the news media as representing an objective view of what’s going on in the world. Still, we use the same word.

Somehow this exhibition collapses all those meanings together and allows us to think, on the one hand, of the newspaper as a creative medium (something South Africans are very aware of because of the recent history of censorship under apartheid), not an objective one (as is the common conceit of the American media). It’s a medium that gives you a vision of the world that has claims to objectivity, but is at the same time a constructed fiction. And, on the other hand, it allows us to consider art as a political or representational medium.

One particularly striking image from South Africa can give some of us insight into the history of work like Siemon’s. [Peffer shows a slide of the censored front page of the South African newspaper The Weekly Mail, 1986.] This front page is from 1986, around the time of the tenth anniversary of the Soweto Uprising. Cultural groups were starting to win the war against apartheid, and there were exhibitions and street marches planned for June 16, 1986. When the media tried to cover some of these events, many of the stories were banned. So the following week The Weekly Mail, a leftist paper at the time in Johannesburg, decided that, in order to keep their integrity, they would run the paper with the black bars that the South African government censor had drawn on the paper. So there are twenty pages of this sort of thing. [Laughter] In some ways, it is a conceptual art piece in itself.

By revealing and therefore highlighting sections of the newspaper, I think what Siemon is doing here seems to be very much the opposite of those censorship bars in The Weekly Mail. But maybe we should also consider what they have in common. Does the act of placing The Washington Post and The Washington Times side by side in an objective gridlike fashion reveal that the newspaper is, despite what journalists aspire to, not as objective a medium as one would think? Is it more like a “beeld,” a representation in the same way that we think of paintings or sculptures as representations? Is the newspaper, although it behaves as a thing that is presenting the objective truth, a created product itself, a fiction?

Rodger Streitmatter: With the concept of objectivity that John raises in mind, it would seem that there should be many commonalities between the kinds of stories that are run in various newspapers. [Powell shrugs.] Is that reflected in what we see?

Adam Clayton Powell III: In 1994, the Freedom Forum did a study of A-sections from various newspapers: The New York Times, The Los Angeles Times, The Washington Post... and some very well respected regional newspapers: The Des Moines Register, The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, The Dallas Morning News. And what was amazing was how little world and national news there was in a respected regional newspaper. Once you go outside of New York, Washington, and LA, and look at the total number of column inches available in the A-section, the word count is the same or less than the number of words in a typical thirty-minute network evening news event. We stumbled onto something, and newspapers set the tone here. People don’t want world and national news; just give them a deck of briefs, concentrate on one or two stories, and that will hold them.

And on the commonality point, what we saw was that papers didn’t have the same news stories. In Des Moines, the Register covered the war in Chechnya more than any other paper, except The New York Times. The Des Moines Register?! [Face scrunches up] “Well, we have a lot of wheat sales to Russia!” Ah!

You look at The Dallas Morning News, and they had fantastic coverage of the Mexican peso crisis—this was January 1995. “What happened down there?”

“Well we consider Mexico a local story!” [Laughter] “We have a four-person bureau down there!”

And then we get to The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, the paper that was the most controversial when we presented these findings at the American Society of Newspapers. Because by far their most dominant story in January of 1995—a majority of column inches, a majority of words, hundreds of photographs—was the OJ Simpson story. And their editor would say, “You’re trying to frame me!”

I think that editors in all or most cases were not entirely conscious of what they were doing. And so what you’re seeing here in this installation is a type of Rorschach test of the editors of The Washington Post and The Washington Times and what they think is important—and they may have less in common than you think.

Streitmatter: [Gesturing to one article] Over there we have a guy who is paying twenty million dollars to become an astronaut, which, I would argue, is fairly prominent in The Washington Times. I believe two photographs are shown. I didn’t see any photographs in The Washington Post. Which I would suggest might reflect a difference in emphasis or readership interests.

Siemon Allen: Ironically, it does in fact occur in the Post, but only in the “World in Brief” section and without an image. But yes, in the Times it is a front-page story with a color photograph. Interestingly, a couple of days before that article came out, the Times also had an article in the diplomatic section talking about U.S. aid to South Africa. I thought it was quite interesting that the total budget was twenty-three million dollars, and I think it had just been increased to twenty-six million dollars. It seemed significant a couple of days later then that this South African entrepreneur would pay twenty million dollars to go into space.

Audience Member #1: Is that the story then? I am playing devil’s advocate for a moment. Do you want us to look at these stories and form some sort of critique of the fact that the Times gives prominence to this affluent, successful, white South African?... Is that more of a story?

Allen: No, for me, the way the story is presented in the Times is rather benign. I don’t think there is any critique there. He is just like the American astronaut/businessman who went up a couple of months before. It comes across as, “Well, here’s this crazy thing, people going into space for space tourism.”

I did read in several South African papers that there was initially some local criticism of his actions. Given that the levels of poverty in South Africa are very high, that seemed like a massive budget to just go and blow on a joyride. But the government eventually came around to the idea, realizing that it would get good media coverage, and I guess the fact that he is on the front page of The Washington Times says something about that. Whether or not that actually produces results for the government, like more tourism to South Africa . . . I don’t know.

Audience Member #1: But in terms of this debate, it certainly boosted their South African coverage in this gallery.

Allen: Yes, and in fact it is one of the few times that the South African flag appears in color on a front page. This is especially interesting in terms of imaging, which is essentially what this piece is about. It is a new flag. If you talk about trying to get those kinds of images out into the media so that people can say, “Oh, that’s a South African flag,” and learn to recognize it as they do, say, a British flag or an American flag, then I think it works. Although, admittedly, it is only half the flag!

Peffer: I have a question. [To Powell] You talk about the local desk and the content that it produces based on what that reporter thinks is newsworthy. I think it is also interesting, in this context, that our attention is drawn to how readers select certain things out of the paper. And, of course, we are also to some extent voiceless in this process, relying on, as we are, what I would refer to when I speak to my students as the “hegemonic content”—a sort of overlay of the conventional view of what is acceptable or desirable to talk about in terms of South Africa from an American perspective.

Do our preconceptions as Americans of what South Africa is, or any country for that matter, determine the kind of content that makes its way into our newspapers? And given that terrain as a baseline, is this work about how each of us looks at a paper differently and chooses certain things out but doesn’t read other sections? When in South Africa, I read all the American content in the papers. I was trying to find out stuff that was related to me, directly or indirectly. Some people just go to the sports page and that’s that. Readership is just as important to consider, especially when it goes against the grain (as it does often) of so-called local editorial decisions.

Streitmatter: Part of the future of the news media may be that we will have “organs” that are tailor-made for each of us, so that I will have certain articles and you will have other articles. And so the news will be tailor-made for me. That very well may happen.

Powell: But figure the extreme of that, which was the case in apartheid South Africa. When I first started going there, they had what here in the U.S. we would call “segregated newscasts.” There was the television newscast for whites. There was another one for blacks. There was another one for Asians. And they were all produced from the same newsroom. And so I videotaped them all and brought them back, and people would just be amazed to watch these newscasts. On the same day you would have very little in common across the newscasts. The newscast for whites had the environment, the economy, and international stories. The newscast for blacks had crime and I guess what you would call “down-market tabloid.” It was the same newsroom, same camera crew, same editors, but different visions of the very same place: their country.

Kirkman: Rodger, I want to ask a question of you. As a professor, how would you use this as an assignment for your classes? To me, it would force students to think about how they read and absorb the news. What it means for them to be intentional about the reading of the news; how they think about what’s left out of both these papers, because that is the most interesting thing. By studying what’s here in these details, you have to think about what’s not here at all.

Streitmatter: The question I would raise is, “Is the newspaper doing its job? Has the newspaper failed if it doesn’t reflect the many different aspects of a particular topic?” It’s a tall order to expect a news organization to reflect the realities that are out there. And in any newspaper can we really say that we reflect everything that is going on? I mean, at the moment the sniper is the dominant story and is certainly what is on my mind, but are there other things going on in the Washington area at the same time? Probably!

Anyhow, I want to shift gears for a moment and talk about some of the decisions you made in this piece. [To Allen] The tracing paper is an interesting choice here. It’s not opaque. It’s not fully transparent. What does that say?

Allen: Originally, I had considered exhibiting the piece without the tracing paper. But when I set it up in the studio, it came across as an unfocused information overload and it didn’t look that interesting. So the tracing paper was chosen partly for aesthetic reasons. At the same time, it allowed for the play between what was foregrounded and what was partially obscured. It acted as a device guiding the viewer to the article on each page. It was also a way for me to highlight each article in a noninvasive way—that is, without damaging or cutting the original newspaper surface. The cut sections frame the articles or sections of articles, while the partial transparency of the material enables the viewer to scan through the other articles of the day, thus contextualizing the South African information in terms of other world events. For me, the pages that are most successful are the ones where there is only a small mention of South Africa, so you just get this little fragment of information. Those are more interesting than the full articles. More poetic.

Powell: Why?

Allen: These fragments seem closer to Brion Gysin’s and William Burroughs’s notion of the “cut-up.” While nothing in this piece other than the tracing paper has been cut, I do think it references or perhaps pays homage to their idea of creating a new poetic language by cutting up preexisting found text sources. The method of the cut-up isolates phrases from their larger original text, making them anew. As with the cut-up, my revealed fragments become disconnected from the originals. The full articles, on the other hand, seem to operate more didactically.

Returning to aesthetics for a moment: I do see two separate but equal (and maybe even contradictory) ways that this piece can be read. On one level, there is the political or social, and on another, the aesthetic. My other reasons for using the tracing paper were that it made the newspapers a sort of creamy-gray color and I tried to match that color to the background/supporting frames. One thing that was on my mind was the strong history of abstraction in painting. I tried to approach the presentation of these artifacts with an awareness of the history of painting. For some time now, I have been working with fields of information, whether they be masses of stamps or large woven screens of videotape; in all my works the grid dominates. Though the complex pattern in the newspapers is the result of the chance isolation of articles as they appear, it still forms a pattern. The panels of papers still display a distinct palette with subtle tones. Formally, in some ways, I see the work as being in conversation with aspects of geometric abstraction.

Powell: But it is found abstraction. It’s abstraction that you have teased out of this artificial presentation.

Allen: Yes, and I use chance quite a lot in the work. I am totally open to that. The more advertisements and bits and pieces of funny color, the better. In the course of constructing the grid for The Washington Post and The Washington Times versions, I noticed what I saw as an alliteration of certain images, such as the repetition of particular advertisements, for example, the aircraft fighter, which I think is for Northrup Grumman. It is actually repeated two lines below on a separate page, and a similar thing occurs with the Lockheed Martin advertisement. It was also interesting for me to consider these so-called arbitrary images in terms of the larger narratives that are ongoing in the newspapers: the “war on terrorism” and the post-9/11 environment. These are bits of information that I do think work subliminally.

Another advertisement in the the Times for nuclear power plant security has quite a disturbing image of a large security man with an M-16 rifle. This reminded me of the kind of images I would see in South Africa, where security is the number one industry.

Peffer: Why the grid? And are these papers arranged chronologically?

Allen: Originally I intended this to be a linear, chronological installation where you could read one page at a time. But the space constraints would not have accommodated this, and I wanted to get as many papers in as possible. I considered going all the way to the ceiling, but that approached wallpaper. The grid is an art convention, and it comes up again and again in my work: the woven videotape works, and certainly the stamp project displays.

Blake Gopnik: I think it is awfully important to consider the things that Siemon was just saying about the look of the piece, about the kind of decision-making that goes into the look of the piece. It emphasizes how much this is a work of art, and how it is contextualized as a work of art. And that makes it almost a completely different beast than in the sense that we have been treating it. It isn’t about newspapers in a straightforward way. It’s not about issues in the media. It’s not about the things you would expect, say, someone in a journalism school to investigate. It’s not essentially about that. That may be its subject matter, but that’s not in a profound sense its content. And I think to really come to grips with the piece, you have to look at it within the context of other works of art. That’s where works of art seem to live most happily to me. And I think it’s a mistake—and this can happen with a lot of work that has a political subject matter—to see it as somehow transparently conveying its content and to take it out of the context of the other art. There are a hundred different ways in which this is very much a part of art that has nothing to do with this subject matter.

Streitmatter: But can it be both?

Peffer: I think it can be both. For instance, Siemon invoked the history of the cut-up technique and montage. The early ancestors of these modernist art practices were formed out of the desire to represent reality as it was understood by people at the turn of the last century. In particular, the gridlike organization of newsprint and the mass production of images in a cacophonous, rapidly industrializing world had a profound effect on the work of Cubists, Futurists, early Dada, and others of their time. There were critical debates in the 1930s about what a “realist” art would look like. Some would say a realist art could only be produced using a cut-up type method or a montage-based art, because the newspaper, and modernity itself, was already producing reality in a juxtapositional form.

So I think it is very valuable to focus in on the cut-up technique as something that is already operating in the newspaper. From that perspective, Siemon’s art reveals something hidden about how the newspaper does its work on its readers via form, and vice versa. A background in modernist art technique enables us to see the kind of cutting and juxtapositioning that occurs in the newspaper everyday. Maybe we should all have a background in modernist art technique in order to enjoy the newspaper these days! [Laughter]

I would like to add that also, any time you read, for instance, an article on Peru and you single out some South African content because perhaps it is what is most familiar to you, is this not that dissimilar from how you would look at an artwork and search for what you already know as opposed to what might be new in it?

Kirkman: I think that’s right. Dziga Vertov’s The Man with the Movie Camera was about teaching people to watch movies, and in a sense this is an artwork that is teaching people how to read the newspaper.

Audience Member #2: Now I am going to be the devil’s advocate. An unspoken aspect here is that more coverage is somehow more responsible, better than . . . that there should be no tracing paper here. I think that presents a problem. Because what you are doing by using the tracing paper is suggesting that it should be all South Africa, all the time. Do you think there should be more coverage of South Africa in the U.S. press?

Allen: Oh no! I am fully aware that the piece might be perceived as a type of egocentric-nationalism, if you will. I use the South African issue because I am South African. On one level, this piece for me is about a personal investigation . . . information-gathering curiosity. When I started the project I assumed, first of all, that there would be many fewer articles. I was actually surprised by how many articles there were. My original assumptions were contradicted. Second, I assumed that most of the coverage would doggedly talk about apartheid and AIDS. In some papers, like The Washington Times and The Des Moines Register, this was not the case. That’s a bit of information I would not have known had I not embarked on this project. And so I would say that this piece is educational, if nothing else.

Sarah Finlay: I think that this is a dialogue about personal and historical memory. I don’t think that the implication is that it should be “all South Africa, all the time.” That is not practical or feasible. For me, it’s about taking a whole year of our press coverage of South Africa, looking at it at one time and discussing it. If it is didactic, it is showing us that we have a limited view of the world. It’s about a personal construct that we make of another place and about allowing us to ask ourselves, “Where does that construct come from?” I think we as Americans see ourselves as isolationists, and this contributes to some degree to a kind of defensiveness and hostility in our immediate reactions to

a piece like this.

Streitmatter: But those of us with a news media background also realize that the amount of international coverage is diminishing. And whether it is reflected in what we see around us tonight or not, we know that it is true. There is an increasing amount of attention paid to domestic issues and not nearly as much to international issues. And maybe that is part of a reflex action.

Audience Member #3: I was just going to say as a nonexpert in the media and as a “normal” American from the South originally [Laughter], I quite frankly haven’t spent a lot of time thinking about South Africa. Certainly I am conversant in the major issues about South Africa, and I keep up with the daily media news in magazines and that sort of thing, but what this has done is really posed an interesting question for me in terms of looking not only at the coverage in the newspapers, but trying to see it through the eyes of a South African. To see where the coverage is actually positioned in the newspapers and what that coverage is surrounded by. It is almost always buried on page 34 or 45 and positioned next to advertising. It is surprising to see how little coverage there is and what gets covered . . . little snippets here and there . . . lots of coverage on sports and HIV. I think this work does a very effective job of showing us that. Obviously, I don’t think anybody would make the argument that it should be all South Africa, all the time.

Allen: To conclude this debate around the question of “Why South Africa?” I think its selection acts as a metaphor. It doesn’t have to be South Africa to make the point. The point is that in taking one aspect of the paper and highlighting it, I am hoping that when people read other articles they would come to those articles with the same sort of criticality. When one looks at the paper tomorrow, how is any other given country defined or imaged here in the United States?

Powell: We could also look at the very artificial way that the newspaper is constructed.

Kirkman: Adam said earlier that at the Newseum they used a system of automated word counting. One of the things that this show represents is our experience of the digital environment, because we can now spider, index, and automatically summarize all these articles almost instantly. I am part of a project called oneworld.net that summarizes ten thousand articles a night, and for me, in a sense, this project is an externalization of what is possible digitally. It forces us to think about how that digital apparatus can be deployed and what kind of critical stance we can take in this overwhelming world of information—this inundation that we have in front of us. I think you are right in that it is not specific; it is about a critical stance. It’s about intentionality in terms of how we understand the news and use it. In a sense, what you are doing is reflecting now what’s possible digitally and that we must think about what that digital environment could mean to us.

Streitmatter: Nice final thought looking into the future! Thank you. [Applause]

|

newspapers (dispatch), st. louis post-dispatch,

newspapers (dispatch), st. louis post-dispatch,

post/times, invite, 2002

post/times, invite, 2002