authentic/ex-centric cover, 2001

aliza levi, samkelo matoti, jay horsburgh, thomas barry, siemon allen

33° x 33°

a one-day dérive into the kwa-zulu natal midlands, 1994

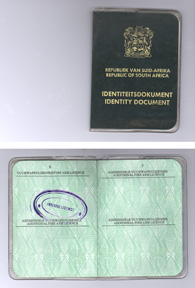

stamps, flat, durban, 1994

walker paterson, w

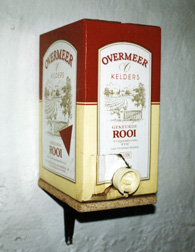

ine-box cardboard, flat, durban, 1994

adrian hermanides, forecast of human trembling, flat, durban, 1994

ledelle moe, forecast of human trembling ii, flat, durban, 1994

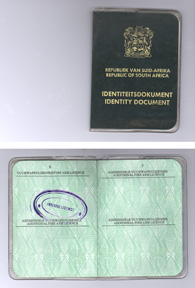

thomas barry, artistic lisence, flat, durban, 1994

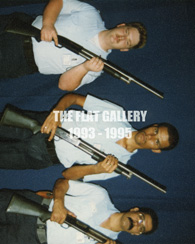

a minor retrospective, flat, durban, 1993

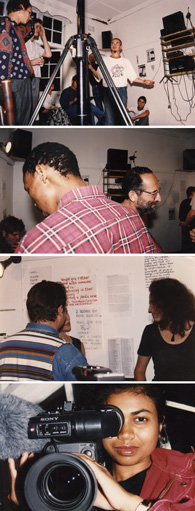

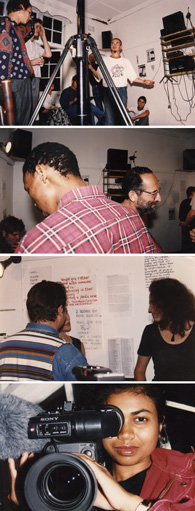

the first internotional theatre of communication, flat, durban, 1994

untitled (from what your case? exhibition), trunk, burnt material, kwamuhle museum, durban, 1995

|

THE FLAT GALLERY

Conceptual Practices In Durban, South Africa

by Siemon Allen

from AUTHENTIC/EX-CENTRIC—Conceptualism in Contemporary African Art

Salah Hassan & Olu Oguibe (eds)

, 49th Venice Biennale, 2001

One day in July 1994 Jay Horsburgh, Aliza Levy, Samkelo Matoti, Thomas Barry and I drove into the Midlands of Kwa Zulu Natal - moved by some compelling curiosity to find and for a moment physically occupy the point represented by 33 degrees latitude and 33 degrees longitude on our map. It was a collaborative ‘action’, a group effort formed out of individual motivations that were at times distinct and perhaps even contradictory, and yet not necessarily incompatible. It began in part a half-cynical ‘pilgrimage’ to find what was rumored by ‘believers’ in Durban to be the sight of some sort of energy ‘vortex’. There was also the slightly more serious interest in bringing about a collision between the artificial orderliness of an intersection of abstract lines on a page and what would be for each of us a distinct and particular lived experience of a previously unknown place.

But, at the time we also regarded our drive as our own kind of ‘derive’, described by Guy Debord in the Internationale Situationniste #2 in 1958, as a “transient passage through various ambiences” entailing “playful-constructive behavior and awareness of psycho-geographical effects”. (1) And indeed ultimately it was this reading (or misreading?) of our action that emerged as being most fitting - for we never found what had been our original goal - our constructed endpoint. En route we got lost and went adrift onto chance encounters. We came upon fenced dead ends and long empty roads that intersected gathering places marked by crowded bottle stores. We met a petrol attendant who spoke to us in French. Our action was ultimately less about reaching any given place or the finality of a set goal than meandering through random meetings and experiences.

What was one to make of five South Africans responding to a charge from a French theorist to create social activism by “dropping their usual motives for movement and action, their relations, their work and leisure activities, and letting themselves be drawn by the attractions of a terrain and the encounters they find there”? (2) And what was one to make of the fact that such an action took place not in the urban back streets of a European city, but in the patch-worked territories of rural areas and small villages west of Durban, South Africa? We were participating in something for which we likely had no clear definition, but regarded as being part performance, part conceptual art work. And, it was in largest part an attempt to collectively question how we might live creatively and actively in what was rapidly becoming a new South Africa. We were indeed “disrupting our normal social patterns” (3) as Debord had prescribed, but within a particular historical and cultural juncture. To move through the city of Durban (as we later did on subsequent ‘drifts’ or “derives”) or to venture into the surrounding social landscape, was to traverse geographies that had been defined and maintained as distinct regions - ones that were fraught (for those of us who found ourselves on opposite sides of this ‘fence’) with a palpable sense of inaccessibility. To embark on a ‘drift’ in South Africa was to cross and re-inscribe what had seemed in its persistence to be an indelible partitioning, and to recognize that whatever other conceptual art practices we might seek to borrow from ‘the West’, they would not travel without significant shifts and torques.

To consider how in the years immediately prior and after the election of 1994, artists in South Africa, and in this case particularly Durban, began to explore the strategies of what might be called ‘conceptualism’ is to look not only at what form such practices took, or question by what historical precedents they were informed, but also to consider how these were explored in ways that were specific to the place and the time. ‘Conceptualism’ was not a singular movement or methodology, but a loose bundle of what were for us new possibilities for actions and interventions. In moves that were often awkward we found ourselves shifting away from the production of an art that had, in spite of its ‘political’ content, been operating within the traditional vocabulary of painting and sculpture into an artistic language that better articulated our experiences.

This shift was perceived by us to be a definitive and rapid break from the ‘resistance art’ of the previous decade - unambiguous narratives spoken through the language of protest. It was as if our crumbling isolation and a new international dialogue made possible a broader conversation both within the country and the larger global community. Something opened up and demanded a subtler and more suitable artistic language for the complexities of our shifting ground.

Many of us had read activist writer and lawyer Albie Sachs’s Preparing Ourselves for Freedom, a paper originally written for an in-house ANC discussion abroad and published in the Weekly mail in February 1990, as well as discussions that it stimulated, all published in a collection of essays, Spring is Rebellious. Deliberately provocative, Sachs called for a ‘ban on political art’ and asked whether “we have sufficient cultural imagination to grasp the rich texture of the free and united South Africa that we have done so much to bring about.” (4) He was by no means prescriptive in terms of what form that “cultural imagination” might take, and his critique seemed to aim most directly at an exhausted ‘weapons–of-struggle’ visual language. But he also complained that the “range of themes is narrowed down so much that all that is funny or curious or genuinely tragic in the world is extruded.” (5) In one response artist Kendell Geers had replied, “The alternative is now for art to remain critical of apartheid. At the same time become critical of itself as well as its own history.” (6) Like Sachs, Geers defined this art as something that relies on “ambiguity and contradiction”, but went further to suggest that to remain vital it must be a thing that “continually re-adjusts its strategies.” (7) It was a kind of questioning in which he was at that time indeed engaged and that we as young artists in Durban were beginning to explore in 1993.

In Durban many of our initial investigations into the language of conceptualism were produced within the locus of a loose community of artists operating out of a shared flat on Mansfield Road. The FLAT Gallery, as it came to be called, was a project that began with the ‘founding’ of what we envisioned as an ‘alternative space’ in this small apartment by the occupants, Ledelle Moe, Neil Jonker, Thomas Barry, and myself. It operated from October 1993 until January 1995 when it was destroyed by fire. During the course of its ‘life’ other artists were in residence for varying periods of time- Jay Horsburgh, Sam Ntshangase, Adrian Hermanides, Samkelo Matoti, and many others exhibited or participated including Carol Gainer, Moonlight, Rhett Martyn, Nkosinathi Gumede, Walker Paterson, Melissa Marrins, Thokozani Mthiyane, Griselda Hunt, Brendon Bussy, Zahed Meer, Clinton De Menezes, Jerome Mkize, Piers Mansfield, Faiza Fayers, Nirvana Ranjith, and Lene Tempelhoff.

We acted initially out of a need to take a more proactive approach in creating exhibition opportunities for work that was not market driven and to initiate projects that would allow for an investigation outside of what we regarded as the confines of traditional genres. But even more importantly we were motivated to generate a dialogue around what we saw as potential for a more vital cultural exchange and production.

This came about in ways that were as varied and particular as the diverse body of individuals passing through the FLAT and a broad range of artistic practices flourished.

There were a number of exhibitions that featured the display of paintings and sculptures, installations, and staged presentations of dance or music. The fluid nature of the space led to its free use on one occasion as an emergency practice space for a street ensemble and on another as a rest place and impromptu workshop site for a group of rural school children in town for the day for an awards ceremony.

But the primary program was an active production of documented and undocumented ‘actions’, interventions, work created out of the collection and display of ‘found objects’, participatory events and audio pieces. In a sense the FLAT itself was the core ‘project’, these programs almost seamless extensions from what was a kind of laboratory for ideas. Though the FLAT project began on the model of an ‘alternative space’ (with a mission to mount exhibitions without censure, to maintain a free space and to exhibit without a market driven agenda or traditional authoritarian selection system), our policy of unrestricted content and open format soon fostered a climate that proved fertile for intensive collaboration and interaction, and a rapid expansion into new genres. What was initially planned as a site for experimental programming soon became a very different kind of ‘alternative space’, one that in fact operated 24 hours a day 7 days a week.

The exhibition space, originally a ‘main gallery’ set up in the lounge, spilled over into the living spaces and bedrooms belonging to the continually shifting residents. In a ‘gallery’ that functioned without set hours, the lines between the artists’ daily activities and the projects became blurred. What occurred was nothing less than a breaking down of barriers between our ‘lives’ and our ‘art’, between our living spaces and our exhibition spaces, between what we had regarded as private and what we had assumed was public. In stretching our definition of what art could be we also discovered how observation and participation could be made to merge.

Most evenings there was a loose gathering of individuals, and openings or events often led to conversations between artists and viewers that extended well into the night. Recording of many of these conversations became both documents and audio works in themselves or raw material for later sound work. The Miracle Filter series, the phrase taken from a box of Peter Stuyvesant cigarettes and a word play on the notion of the tape-deck as a ‘filter’ for all our ‘jargon’, included recordings of language games - thrift store books randomly distributed and read to create an audio ‘exquisite corpse’ out of ‘cut-up’ phrases and the collisions of our individual accents - in this case - British-South African, Afrikaans, and Xhosa. Bread and Pliers was an audio letter made by Nkosinathi Gumede for the artist Andries Botha—who was in the United States at the time—telling the story of how he once sold a sculpture in which he had accidentally left his pliers and a piece of bread. Conversation was an improvised banal exchange between Elmin Engelbrecht and myself, a critical parody of what we felt was our generation's politically-detached intellectual laziness, as well as a play on the psycho-sexual complexities in male-female conversation.

Zulu for Medics was created from found raw material found in a pawnshop - a language tape for teaching English speaking medical students how to communicate with Zulu patients. Zulu for Medics became an appropriated ‘audio document’ that in spite of its ‘well meaning’ intentions, spoke volumes about the power relations between a physician and a patient, the colonial authority and the ‘native’ through the ‘probing’ authoritarian tone of the doctor as well as the personal nature of the questions. The work revealed the awkwardness inherent in bringing together two cultures or languages fraught with a loaded history of conflict and mistrust. Many Zulu-speaking visitors found it amusing; so wooden and simple minded did the non-Zulu speaker sound on the tape.

Since for a time all interactions that took place at the FLAT were almost obsessively recorded, the result was a strange, uncensored social document that also provided a rich collection of audio material for used in sound works. While many of these were made with ordinary ambient noises or words, reduced through looping, cutting or altering to create ‘pure sound’, the recordings where speakers’ words were (at least initially) understandable and not yet unhinged from their signifying function, were perhaps the most interesting. In a number of experiments exploring methods first employed by composer Steve Reich (especially in the work Its Gonna Rain and Come Out), recorded words were superimposed and repeated to create a ‘wash’ or collaged phrases combined with found recordings or sounds. These included an audio work constructed from a loop of Moonlight’s words “…ladies just stopping to sell your bodies” and a collage with Elmin’s “…especially the fact that I don’t have a car”. In Nina Paul Nina, an introduction between two individuals was repeated over and over - as if they were caught in a perpetual introductory phase in a relationship - never getting any closer. Though the recordings were never made surreptitiously, the very act of using and re-using what was (both actually and metaphorically) an individuals ‘voice’ uncovered regions of exchange that confronted issues of (mis) representation, permission, ownership and even coercion.

Along with this 'collection and display' of found sounds, display of other found objects was also common, with audio works presented through a variety of visible 'hi-fis' and works that featured items displayed 'out of context'. Barry, for whom the act of collecting was itself an ongoing project, exhibited his archive of discarded playing cards and matchboxes - scavenged from the street - many of them showing evidence of markings and notes from their unknown previous owners, like archival evidence of a ‘throw-away’ history. I presented ‘icons from my youth’- my Hardy Boy books, my outgrown ‘logo’ clothes, and my stamp collection, (which was regarded as a kind of highly mobile visual propaganda.) Walker Paterson irreverently presented a filled cardboard ‘wine box’ in the context of a guest curated ‘paper works’ exhibition and a ‘print’ called Cape Settlers and Color Zerox, a cheap copy of a ‘heroic’ painting depicting the arrival of the Dutch pioneer Jan van Riebeek. It was an image, Peterson observed with droll humor, that he was likely to be hung above the mantle in many respectable South African homes.

In two exhibitions that were scheduled within a few weeks of each other we explored the confrontational power of bringing individuals from the ‘outside’ into installation situations; actors who not only behaved as ‘performers’, but essentially ‘played themselves’ in a theater that operated uncomfortably within the viewer’s space. Adrian Hermanides and Ledelle Moe each constructed works where ‘guests’ from the ‘real world’ were brought in as elements in installations where they self-consciously ‘inhabited’ identities that were recognizable and highly charged for a South African viewer: namely the adolescent school boy and the security police.

Moe and Hermanides, who were both investigating ways in which they might confront what they regarded as heavily charged sexual and political content, used ‘human’ sculptural elements to deal with the tensions between the individual and the institution. Moe was responding to an unsettling experience of visiting a home for the aged and was thus preoccupied with how the acute sense of vulnerability and the obsession with security in the home seemed to mirror those of white South African society. Hermanides was addressing his own issues of sexual orientation through memories of his adolescent awakening in the context of a South African authoritarian all-male school.

In Hermanides’ work viewer’s entered a tight space formed with school lockers and gas burners. On two chairs bolted to the wall were 16 year old, blonde-haired boys dressed in Westville Boys High school uniforms (the same uniforms Hermanides had worn when he was a student there). They sat silent, eyes forward, held in suspension. Moe used small photographic portraits of residents of an old age home address the issue of violence in South Africa and its complex resonance for the privileged and the aged. Requiring intimate viewing, the photos were hung in a cramped room protected by three security guards with loaded shotguns. It spoke to the vulnerability of the elderly, protected by force and by guns, and perhaps also to the obsolescence of these aging South Africans as well as their regime - a loaded metaphor, indeed, in a society where the largest industry is security and violence levels are extremely high. It was an unsettling reminder that the new emerging ‘growth industry’ was in a sense a sad intrusion of the past into the future.

There was much discussion afterward around not only the response of viewers to the work - the discomfort of being participants and in a sense implicated in the ‘action’ of the theatrical sets, but also the complexities of engaging an individual as a ‘sculptural object’, asking a person to essentially ‘play himself’. The boys and the guards were individuals who had indeed been objectified in the process of being ‘cast’. But dressed as they were in uniforms, they were also representative of the objectification of institutions. Any expectations of viewing pictures in a neutral gallery space—the traditional whitebox—were disrupted by the appearance of the hidden security guards, but along with this uneasiness there was also some confusion as to whether the guards were ‘part of the art’ or brought in out of some awful necessity. For us it was an interesting enactment of what we came to see as the power in a performance (or intervention) that does not immediately reveal itself as ‘performance’ and so operates through a certain degree of ‘subversion’, in other words, a ‘situation’.

There were many such interventions at the FLAT. Moe began to pull rough and battered animal carcasses out of the galleries and into ‘the world’, an act that prompted much curiosity and conversation out on the streets. Hermanides cast a boot on site from the bronze public statue of Louis Botha arousing the interest of the (then apartheid era) South African police who offered to assist in what they mistook for a ‘repair’ session. A banner was hung over a concrete overpass in front of the Warwick Avenue railway station, a ‘found’ Technikon Natal sign complete with name and coat of arms was ‘fudged’ to read, “What is Your Response?” Barry made his own official-looking stamp ‘engraved’ with the words “Artistic License”, and invited people to produce their ID books to be stamped on the page that was normally for gun licenses. A visiting artist would repeat a version of this performance, several years later, at the 2nd Johannesburg Biennial.

One of the most elaborate ‘trickster’ interventions occurred when Kendell Geers exhibited in Durban and we orchestrated a ‘faux exhibition’ of his work. We photocopied images from various catalogues, mounted them onto masonite squares and presented them under the title, A Minor Retrospective. Since we printed high quality invitations and put up posters all over Durban, many thought that these had originated from the institution that was sponsoring the artist’s official exhibition. The situation grew more complex and hilarious when at the opening of the ‘real’ exhibition the director was told of a show at the FLAT and mistakenly thought that it was Geers who had prepared that exhibition as well, and thus went so far as to announce to all that there was “more work just across the road”. Confusion continued over the authenticity of the FLAT exhibition, with some viewers debating their preferences for one exhibition over the other. An unintentional, but strangely appropriate occurrence also contributed to the absurdity. In an attempt to remedy our dirty floor at the FLAT, we painted it with fresh, black, enamel floor paint less than three hours before the opening. Of course it did not dry for the opening, and so when the crowds came to view work that no one except the FLAT co-conspirators suspected was not ‘authentic’, they stuck to the wet painted floor. Interestingly, Geers, either out of a disinterested or co-conspiratorial mind, did not deny that the FLAT exhibition was a ‘faux’ exhibition of his work, leaving many viewers with the impression that he had indeed mounted two shows in Durban.

The performative aspect of this ‘faux exhibition’ (and the small ‘dramas’ that were spun from it) functioned through collaborative action. However, perhaps more important was the fact that this action was somewhat conspiratorial and challenged the notions of ‘authenticity’ and ‘reality’. The art on the walls was not ‘real’, and the ‘exhibition’ extended beyond the gallery into the world through an intervention that was subtle and subversive. In a sense, we sought in our rather crude exhibition to ‘converse’ with Geers’s work not only through the obvious ‘plagiarizing’ of his images, but more importantly through the very tactics that we employed.

The First International Theatre of Communication, another FLAT event, began with an open invitation and no real plan except to bring people together with the catalysts of an open microphone, two tape recorders, some provocative wall texts and a space to interact. The only goal was to allow open expression and ‘put a group of people together and see what would happen’ like in Andre Gregory’s beehive. (8) Though initially much of the audience came with the expectation of ‘watching’ a performance and stood waiting to be ‘entertained’, slowly they began to approach the open microphones and the evening evolved. The resulting audio recording produces a sense of odd simultaneous occurrence of so many ‘communications’. There were free association ‘poetics’ spoken through soliloquy, citations and exchanges, formal presentation of audio works, banters with non sequiturs, and more ‘serious’ discussions including numerous complaints about the event itself. A kind of ‘total theater’, a carnivalesque endeavor built on the absurdity of randomly collaged actions, it was indeed a ‘polyphonic’ voice.

By January 1995 the FLAT gallery was beginning to wind down, the strain of the constant demands beginning to take a toll, participants drifting away - traveling or engaging in other projects. But the end was characteristically dramatic. We had already been given notice to vacate the flat at the end of January. A candle left burning by one of the occupants set it on fire and Barry and I drove past the FLAT just in time to see the fire engines and the firemen putting out the last of the flames. It was a fitting finale. Ironically, all that remained was Horsburgh's miraculously unharmed passport and some chars that became our last collaborative ‘readymade’ artwork.

The experience pushed something in our artists’ lives that we had not encountered before and opened us up to a particular kind of dialogue and experimentation that was invaluable in our later development as artists. Our explorations were in many ways an expression of what was then a growing need for us to offer a political critique of our own experiences - to speak sincerely from our own personal perspectives, and yet still address social concerns.

Though it was in many ways a departure from the protest art of the previous generation (a practice that emerged from the political necessity to speak clear and unambiguous narratives) it was nevertheless artistic practice that still spoke out of an urgent political consciousness. As voices that had been previously silenced began to enter the dialogue it became painfully obvious to many of us that we as young artists needed to develop new forms, new means to reconcile the contradiction inherent in speaking to political concerns; and yet not speak ’for’ other South Africans with experiences that we could not presume to ‘know’ and stories that we could not presume to tell. It seemed particularly significant that in the 16-month period of the FLAT’s ‘life’ it straddled precisely the historic elections of April 1994, and thus marked for us a historic transition from one era to another.

NOTES

1 Guy Debord, ‘The Theory of the Dérive’, Ken Knabb (ed.), Situationist International Anthology, Berkeley, Beureau of Public Secrets, 1981, p. 50.

2 Ibid.

3 Ibid.

4 Albie Sachs, ‘Preparing Ourselves for Freedom’, Ingrid De Kok (ed.); Spring is Rebellious, Cape Town, Buchu Books, 1990, p. 19.

5 Ibid,p. 20.

6

Kendell Geers, ‘Competition with History: Resistance and the avant garde’, Ingrid De Kok (ed.); Spring is Rebellious, Cape Town, Buchu, 1990, p. 44

7 Ibid.

8 Wallace Shawn, André Gregory, My Dinner with André, Screenplay for film for Louis Malle, New York, Grover Press, 1981, p. 26-27.

|