|

|

marais/brand, white box, ny, 2001

marais/brand, white box, ny, 2001

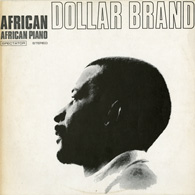

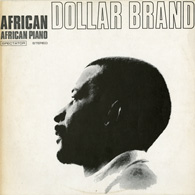

dollar brand, african piano, spectator, 1969

talk, goethe institute, washington, 1999

work (siren), generator, johannesburg, 1996

songs for nella, flat gallery, durban, 1994

|

AUDIO

MARAIS / BRAND, 2001

audio installation

58 minutes 25 seconds

This audio work is essentially an examination of South Africans in the Diaspora and how they operate in and effect the international arena.

The piece was constructed from a variety of appropriations (some transformed more than others.) The music of South African exiled musician Dollar Brand (Abdullah Ibrahim) is set up in counterpoint with testimony from a witness, named Laurentius Marais, who was arguing on behalf of the US Republican Party in the 2000 presidential election case (also known as the Bush v Gore Florida ballot controversy.)

The connections between the original recordings were admittedly rather oblique – coming as much out of contingency as purpose. As a South African who spent a great deal of time in Washington DC, I found myself interested in what I regarded as an ‘overflow’ of press information – particularly on radio stations broadcasting ‘live feeds’ and unedited archival materials. It struck me as how obstacles to public access of information can occur not only through censorship, as had been my experience growing up in South Africa, but also through what was to me a kind of overwhelming deluge of information.

In my studio I worked to the constant ‘soundtrack’ of these ‘news/talk’ programs as well as random playings from my CD collection. One day back in December, while captive to what were hours of coverage of the legal battles in post-2000 election Florida, I heard what was presented as ‘expert testimony on statistical models’ - in order, it was claimed, to interpret what were the complex results of voter demographics and ballot configurations. A witness was called by the name of “Marais”. This is a common European - South African surname which originated with the migration to the Cape of Good Hope of French Huguenots fleeing religious persecution in the late 1600’s. And it struck me as curious when the voice of this individual so identified, with an accent obviously not ‘American’ came through on my radio.

In the testimony Marais, gives statistical evidence that ‘proves’ (in his opinion) that there was no probability that Albert Gore would win the US election if there were a recount. It seemed interesting that ‘statistics’ here had such a profound direct effect on the outcome of a case so central to the election results, and that this particular ‘statistical’ information was so obscure.

In the court proceedings, Marais claimed to be American (he voted in the US election) but in examining his Curriculum Vitae I found that he received his Bachelor of Science (Mathematics, Applied Mathematics, Computer Science) in 1973 at Stellenbosch University. If Marais was indeed South African, this discovery led me to a much broader question of how ‘expatriate’ or ‘exiled’ South Africans interacted with the larger world. And how, in this case, someone like Marais would or could play such an important (and yet seemingly minor) role in shifting world affairs (a US presidential election in which George W. Bush would become the winner in the Marais’ case). At the time of constructing this work (2001) these questions about Marais’ effect on world politics seemed interesting and perhaps academic but in light of recent world events, Marais’ role, in retrospect, becomes more significant.

Early in 2001, I speculated on what circumstances might have made such a thing possible, and thought about how names (as markers of ‘a people’) travel. At the same time I was listening to South African musician Dollar Brand’s African Piano, reflecting on how he had left South Africa, an exile, and that his music was now in my studio, in the same audio space as the drone of C-SPAN radio.

Dollar Brand, who changed his name to Abdullah Ibrahim after his conversion to Islam in the late 1960s, was born in Cape Town in 1934. In 1962 he left South Africa and toured Europe with the Dollar Brand Trio. There he settled in Zurich where he met Duke Ellington, who arranged a recording with his band and sponsored Ibrahim’s first appearance at the Newport Jazz Festival in 1965. From there on Ibrahim would perform alongside some of the greatest jazz musicians. In 1968 he embarked on a solo piano tour and in 1969 recorded the work that would become African Piano, a concert broadcast from Copenhagen. Since then he has been playing concerts and clubs continuously throughout the United States, Europe and Japan with appearances at the major music festivals of the world.

To set up the counterpoint I simply superimposed African Piano over the textual voice of Marais giving this piece a filmic quality. The two audio elements for me represent not only the labours of two South Africans in the Diaspora but reveal how each have intersected with the world and influenced their respective fields exterior to South Africa.

Siemon Allen

2004

from the exhibition AFTER THE DIAGRAM

curated by Lauri Firstenberg and Douglas Cooper

White Box, New York, NY, 2001

|

industrial, rembrandt, johannesburg, 1995

work, generator, johannesburg, 1996

|

MISTAKEN MEDIA

by John Peffer

MARAIS / BRAND, 2001

audio installation

[extract from the website of Minette Vari]

For Minnette Vári and a number of her South African contemporaries the print and televisual media technologies are not merely neutral ideological instruments to be wielded differently depending on who is in power and who is struggling to have their voice heard despite the structure of power. For these artists these images mediated by technologies of mechanical (and now digital) reproduction are perhaps the only way they can come to form an idea for themselves of who they are.

Siemon Allen, who has lived the US since 1996, has been mining the international news media for images of the South African experience. In his recent audio art, Allen, who now lives in Washington, has located the "South African" voice in NPR broadcasts during the botched Florida presidential vote-count. The result is Marais/Brand, a mixture of white noise from Lyndon Johnson's phone conversation tapes, musical samplings from South African exiled pianist Dollar Brand, and court testimony by a man named Marais - the republican party's statistics expert during the Bush/Gore fiasco - all these things were heard by the artist while working in his studio. The American context is abstracted, or silenced for a moment, in each case: Dollar Brand is "here" but playing "African Piano" - the Johnson Tapes are just used for their static - and we only hear the answers, not the questions posed to Marais - a man whose accent, and Afrikaner name, ought to make one wonder how a white South African, from a country where statistics were used for racialist ends for 50 years, could possibly be an expert on a Florida ballot, itself divided along racial lines.

This audio work is Allen's effort to find himself, or traces of a conflicted South African experience familiar to him, in the overwhelming flood of petty information coming over the radio during the long presidential election. Somehow, amidst the barrage of information, we can hear a struggle for the soul of South Africa, in the head of a countryman abroad. At moments it seems as if Dollar Brand's frenetic playing is desperate to shout down the monotonous drone of the statistics expert's voice.

John Peffer is a visiting Assistant Professor of African Art History at Northwestern University.

view full essay

|

talk, goethe institute, 1999

talk, goethe institute, 1999

|

TALK, 1999

audio installation

[exract] South African artist, Siemon Allen, constructs both sculptural and sound installations to create works that deal with the nature of boundaries and shifting context. Here he continues these explorations with two new works: Talk (1999) and Fence (1999).

For Talk, installed in the darkened industrial downstairs gallery space, Allen combines cut-up sounds from Washington, DC talk radio programs with a large architectural structure. As a South African, Allen was especially interested in the relationship between public radio 'open lines' and the concept of 'free speech'.

Emitting from the vaguely perceived interior of an impenetrable black box, isolated questions from radio hosts - Diane Rehm and Kojo Nnamdi - are presented without guest replies to the gallery audience. Each question is framed by a rather lengthy interval of silence. It is work that confronts the viewer with frustrated entry and questions left unanswered.

from the exhibition broshure text for IMPORT

by Markus Withmann and Siemon Allen

Goethe Institute, Washington, DC, 1999

|

work, generator, johannesburg, 1996

work (siren), generator, johannesburg, 1996

work, generator, johannesburg, 1996

|

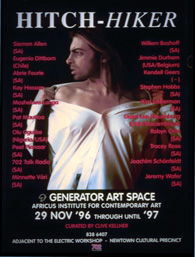

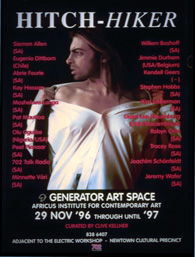

WORK, 1996

audio installation

Work was included in Hitch-Hiker, curated by Clive Kellner at the Generator Art Space in Johannesburg. Continuing an interest in audio, I installed a functioning work-siren in the gallery space. I was interested in the fact that an essentially ‘abstract’ sound (as that made by the siren) could be fraught with many deep social references and/or implications. My aim was simply to superimpose this time-regulation device, common to the labour-force in industrial areas, onto the ‘other world’ of the gallery. It also seemed appropriate that this exhibition venue, the Electric Workshop, had previously been an industrial work site.

The installation consisted of two parts: the timing device and the siren. The timing device was set up in the main exhibition space corresponding with the positioning of the other art works in the show however it was installed in such a way that it could be dismissed as just another electrical device in the space. The siren remained almost hidden 10 meters above the main mechanism.

The timing device was set to go off every hour on the hour during office hours for the duration of the exhibition. It did not sound over the weekend. The range of the siren was 3 km and sustained itself for roughly 20 - 30 seconds. Visitors to the gallery could come a number of times without hearing the piece, thoug if you happened to be there at the 'right' time it was certainly deafening especially installed indoors.

Work was also exhibited on the 2nd Johannesburg Biennale: Graft at the South African National Gallery in Cape Town.

from the monograph, SIEMON ALLEN

published by FLAT International, 1999

HITCH-HIKER

curated by Clive Kellner

Generator Art Space, Johannesburg, South Africa, 1996

Eugenio Dittborn. Abrie Fourie, Kay Hassan, Moshekwa Langa, Pat Mautloa, Olu Oguibe, Peet Pienaar, Minette Vari, Willen Boshoff, Jimmie Durham, Kendell Geers, Stepen Hobbs, Kim Lieberman, Grant Lee Neuenburg, Robyn Orlin, Tracey Rose, Joachim Schonfeldt, Jeremy Wafer, Siemon Allen

|

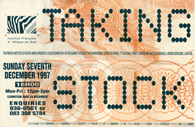

taking stock poster, johannesburg, 1997

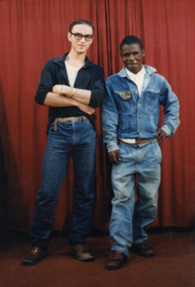

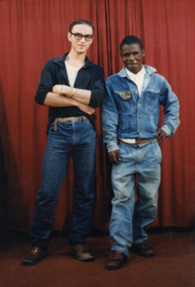

barry & moonlight, 1994

|

SELL YOUR BODY (AFTER REICH), 1997

audio installation

11 mins 13 secs

Voice: Moonlight

Original recording made by FLAT Recordings, Durban, 1993

Original version of Sell Your Body, 1995

This version digitally re-mastered by Michael Hamady, ALPHA BEAT, 1997

This sound work was produced from a conversation recorded amoung many that took place in 1993 at the FLAT Gallery in Durban. At that time, a group of artists (including myself) were obsessively recording all social interaction that took place at the FLAT. These recordings were made without censure or specific intention, following only the urge to record (as neutrally as possibly) the found sounds of this environment, so as to produce a 'purposefully' uncritical social document. The resultant tapes (as in this case) were then used as raw material for further sound pieces.

In one such tape, the speaker, Moonlight, a grounds-keeper from the Natal

Technikon expressed his opinions on the subject of prostitution:

Black ladies, just stopping to sell your body!

White ladies, just stopping to sell your body!

Indian ladies, just stopping to sell your body!

...er...Coloured ladies, just stopping to sell your body!

These words revealed a complex dynamic of relationships across gender and racial lines; however, the repetitive pattern of these phrases also asserted themselves on a purely formal level. Some months later, when I began to use the collected raw audio material to generate sound works, I revisited this conversation with Moonlight and 'looped' the sample quoted above. The original audio information was subsequently superimposed upon itself numerous times, so as to produce a work that began with recognizable words, and then progressed into a 'cacophony' of sounds.

My initial influences for this process lay in the technical experiments of American composer Steve Reich, in which he constructed a 'new music' entirely from recorded words. Significant was the fact that not only did he appropriate and manipulate voices in his work, but in two very important pieces - It's Gonna Rain (1965) and Come Out (1966) - the voices of black men.

read more in A BLACK VOICE below

from the wall text for the exhibition TAKING STOCK

curated by curated by Marco Cianfanelli, Andrea Bürgener, Luan Nel

Johannesburg Stock Exchange, Johannesburg, South Africa

|

what is the value...?, technikon gallery, 1994

This audio installtion consisted of a grid of 180 telephone numbers with a speaker system installed behind. The Yellowbook with CD below is the document of the installtion.

what is the value...?, technikon gallery, 1994

what is the value...?, technikon gallery, 1994

yellowbook, nsa gallery, durban, 1995

yellowbook, nsa gallery, durban, 1995

yellowbook, nsa gallery, durban, 1995

yellowbook, nsa gallery, durban, 1995

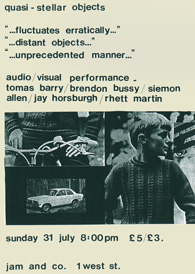

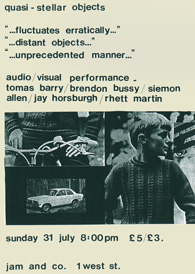

quasi-stellar objects poster, jam & co, 1994

Quasi-Stellar Objects was a multi-media performance event that was the culmination of all the audio experiments we had explored at the FLAT Gallery. It took place at Jam & Co, Durban's preeminent afro-jazz club and featured Brendon Bussy, Thomas Barry, Jay Horsburgh, Rhett Martyn, Willem Huysers and Siemon Allen.

quasi-stellar objects, jam & co, durban, 1994

quasi-stellar objects, jam & co, durban, 1994

quasi-stellar objects, jam & co, durban, 1994

quasi-stellar objects, jam & co, durban, 1994

quasi-stellar objects, jam & co, durban, 1994

quasi-stellar objects, jam & co, durban, 1994

quasi-stellar objects, jam & co, durban, 1994

|

GREY AREAS

edited by Candice Breitz and Brenda Atkinson

In 1997, a debate had been ignited in South Africa over the representation of the ‘other’, specifically around the work of Candice Breitz, Minette Vari and Penny Siopsis. It began when Okwui Enwezor, the curator for the 2nd Johannesburg Biennale, wrote an essay in a Norwegian catalogue for an exhibition on South African art, criticizing these white artists ‘use’ of images of black women. Kendall Geers echoed these sentiments in a review for The Star, and an extensive response from Breitz followed. With this, an aggressive debate was catalyzed, and Breitz, along with Brenda Atkinson invited artists to contribute their perspectives on this critical topic for a collection of essays titled Grey Areas.

I chose to submit an essay that dealt with the issue through reference to the recording of Moonlight’s voice at the FLAT Gallery, and my subsequent use of this in a sound work. My attitude about the use of his voice in this particular audio work was at that time extremely ambivalent, and so this catalyzed in me the effort to try and articulate some of my thoughts on both the work and the question of representing the ‘other’. A BLACK VOICE was written in November of 1997.

A BLACK VOICE

by Siemon Allen

It has been with great interest that I have followed the recent debates around the issues of representation. I believe that cultural production within the particular historical conditions of post-apartheid South Africa throws into sharp relief issues that have broader relevance in a post-colonial world. More directly, as a South African artist I have found myself confronting these issues in my own work. This was most apparent when I created a sound work that involved the appropriation (both metaphorically and literally) of the ‘voice’ of a black African man. I was forced to address the complexities and contradictions that arise when one begins to speak across what was once an impenetrable wall. And then, in a effort to build on that ‘conversation’ one finds oneself engaged in what can easily become a form of suspect representation of the ‘other’.

The roots of this particular work began in 1993 at the FLAT Gallery in Durban, South Africa. A group of artists, including myself, were obsessively recording all social interaction that took place at the FLAT. These recordings were made without censure or specific intention, only the urge to record (as neutrally as possible) the ‘found sounds’ of this environment and so produce a ‘purposefully’ uncritical social document. Often, the resultant tapes would be used as raw material for further sound pieces. While many of these works were built with ordinary sounds or words reduced through manipulation to pure sound, the most interesting were those created when the recorded words were not (at least initially) unhinged from there signifying function. This brought to the constructed sound piece both meaning and a definite speaker’s voice. Though the subjects were aware of being recorded (so that this was never a surreptitious enterprise,) the very act of using and reusing voices other than my own was problematic in terms of (mis)representation, permission, ownership or even coercion.

At that time the FLAT had evolved into a space where artists gathered to work and exhibit. It had a free-flowing atmosphere with people coming and going. In apartheid South Africa it was not insignificant that this included a diverse group of participants. One conversation recorded among many took place during a typical late night session. Four men (all South African) engaged in what was a rather ‘ordinary’ late night activity for young men - drinking too much and talking about politics and women. What was not ordinary by apartheid era South Africa was the fact that one of the men, Moonlight, was black.

A grounds-keeper at the Natal Technikon, Moonlight had befriended one of the FLAT occupants, Thomas Barry. In a recorded conversation, Moonlight expressed this opinion on the subject of prostitution:

Black ladies, just stopping to sell your body!

White ladies just stopping to sell your body!

Indian ladies, just stopping to sell your body!

Er… Colored ladies, just stopping to sell your body! [1]

I was struck by these phrases. I would not presume to know what Moonlight ‘meant’, and our meeting was the result of such a rare contingency that we have not met again. Rather I seek to elaborate on the thoughts that his words provoked for me.

That the speaker, a black man, in speaking to women - all women - would address them as Black, White, Indian, Coloured seemed to me to reveal how thoroughly entrenched in one’s consciousness was apartheid’s notorious classification programme. In a system where any single individual was identified first by racial group, it was not surprising at the time that Moonlight would address each group separately. However, it also seemed significant that this ‘roll call’ put special emphasis on the fact that all women were included, and that no woman, whatever her race, was exempt from his warning. Such an admonishment to women from a man might imply respect, yet such a statement also begins to speak for women. The implication is: “Women should not…” and so reveals the complexity of a man speaking for women (his ‘other’).

That Moonlight had spoken to women and addresses each group separately revealed a complex dynamic of relationships across gender and racial lines; however the repetitive patterns of these phrases also asserted themselves on a purely formal level. Some months later, when I began to use the collected raw audio material to generate sound works, I revisited this conversation with Moonlight and ‘looped’ the above quoted sample. The original audio information was subsequently superimposed upon itself numerous times to produce a work that began with recognizable words and then progressed into a cacophony of sounds.

My initial influences for this process were the technical experiments of American composer Steve Reich, in which he constructed a ‘new music’ entirely from recorded words. More significant was the fact that he too appropriated voices in his work, and in two very important pieces, the voices of black men. They were a Pentecostal street preacher named Brother Walter, and a youth accused of murder in the Harlem Riots of 1964, Daniel Hamm. In the recording of Brother Walter, Reich used words from a sermon on the Biblical Story of the Great Flood (“Its Gonna Rain”) and by superimposing repeated sounds created a cyclical ‘wash.’ He described the work by calling it “controlled chaos... appropriate to the subject matter - the end of the world.” [2] In this way he participated in the original massage of the sermon. And Brother Walter is given credits in the liner notes.

The second example operated in a very different way: it also appropriated the ‘voice' of another, but was originally produced, in part, for a benefit on behalf of the individual whose voice is heard. Reich describes the sources for the work Come Out in the liner notes of the CD:

Composed in 1966, it was originally part of a benefit presented at Town Hall in New York City for the retrial, with lawyers of their own choosing, of the six boys arrested for murder during the Harlem riots of 1964. The voice is that of Daniel Hamm, now acquitted and then 19, describing a beating he took in Harlem’s 28th precinct station. The police were about to take the boys out to be ‘cleaned up’ and were only taking those that were visibly bleeding. Since Hamm had no actual open bleeding he proceeded to squeeze open a bruise on his leg so that he would be taken to the hospital. “I had to like open the bruise up to let some of the bruise blood come out to show them.”[3]

Both the appropriation of another’s ‘voice’ and the formal manipulation of that voice are problematic. When words are reduced to pure sound there is risk of loosing the potency of their original content. Yet it is significant that Reich’s work has overtly ‘political’ content and function created in the spirit of a ‘protest’; it is done for the benefit of another whose voice is ‘taken’. While work of this kind protests the suffering of another, it unintentionally reveals the divide between the experience of the one who ‘speaks’ (the artist) and the experience of the one ‘spoken of’ (the subject.) Is there merit in a work which allows the voice of another to be heard, but does so through manipulation. Is that merit somehow negated when formal manipulations ‘aestheticize’ these words into abstract sounds? Do such efforts speak accurately for the appropriated voice and if so with respect? Are these concepts ‘speaking for’ and ‘respect’ mutually exclusive? Reich’s abstracted sounds, appropriated from the voices of others, may be problematic, yet what would have been accomplished by leaving these voices silent?

These questions are resonant with the contradictions that were inherent in the so-called ‘resistant art’ of South Africa (from the 70s and 80s). The fact that the work of many White artists of this period was produced at a time when to remain silent, or not to speak of the ‘other’ in the face of outrageous injustices, would have been immoral. The alternative, to retreat into academic formalist abstraction or sanitized images, would have been unconscionable. Though justifiable at the time, some of these strategies may have been outgrown. Perhaps they now require a sensitivity to the complexities of ‘speaking for’ and ‘speaking of’. Clive Kellner addresses this when he points out that “speaking from one’s own position, not through that of the Other, will contribute to a heterogeneous, yet cohesive social politik.”[4]

And yet I wonder if it is it possible (particularly in race-obsessed South Africa) to speak solely ‘of oneself’ without implicating the ‘other’? How can any self-critical process not make reference to that which is intrinsically present in its critique?

Indeed, to deny individuals who occupy any particular ‘side’ (across gender, race or economic lines) access to representation of the ‘other side’ is to obliterate their mutual interaction, (even if that interaction be problematic.) The issue is perhaps not a question of ‘who has the authority to represent whom’ but rather, a need for more voices in the debate.

In exposing the contradictions that lie in any construction of ‘self’ and of ‘other’ we may begin to understand the dynamics of ‘otherness’ operating in a changing society. For this ‘otherness’ may reveal itself as a relative thing, not always rigidly located in one’s race, gender, or economic status solely. Rather, the complex composite of factors that make up each ‘individual’ shift with each social interaction and with each formation and reformation of affinities within a group.

The original recording of Moonlight was a document of an authentic social interaction between a black man and three white men. As with many FLAT tapes, the conversation revealed how awkward our efforts can be when we seek to communicate. I look back on that work without any clear resolution as to the ‘correctness’ of such an act, but I am certain that the encounter was significant in its implications. Both the original recorded materials and the resultant sound work are resonant with larger ‘conversations’ that are now taking place. Did I appropriate Moonlight’s voice ill advisedly? To have excluded him from the number of voices that I used (and still use) to create sound works would have been to remove a valid ‘voice’ from the FLAT documents.

[1] Moonlight; ‘New Years Eve 93’, FLAT Recordings, Tape 2, Durban, FLAT, Dec, 1993

[2] Steve Reich; Liner notes from the CD: Early Work, Elektra Nonesuch; 1987.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Clive Kellner; ‘Cultural Production in Post-Apartheid South Africa’, Trade Routes: History and Geography; The 2nd Johannesburg Biennale Catalogue, 1997, p. 30.

from GREY AREAS - Representation, Identity and Politics in Contemporary South African Art

edited by Brenda Atkinson and Candice Breitz

Chalkham Hill Press, Johannesburg, South Africa, 1999

ISBN 0-620-23664-7

|

flat recordings, cds, flat international, 1999

flat gallery, 1994

siemon allen and thomas barry, 1994

|

ALTERNATIVE! ALTERNATIVE TO WHAT...?

by Meredith Vie

FLAT RECORDINGS (1993 - 1995)

2 CD Boxset

[extract]

The now defunct FLAT Gallery, Durban’s experiment in alternative ‘living’ and ‘visual display’ celebrates its third year of surreptitious activity with the release of two eponymous CDs. [...]

Though thoroughly adept in the conventions of installation, the members of FLAT are perhaps most notorious for their uncritical consistency in low-fi audio documentation and it is out of these unorthodox sound files that the two compact discs make their debut. “The principle is that it does not matter what you have to say - but it is vitally necessary that you say it,” says Jay Horsburgh (aka Yaj Marrow) in a flyer propagating the situationist inspired event: The First Internotional Theatre of Communication. And indeed he eats his words as the entire three-hour FLAT extravaganza in information transformation and audience participation is canned into a seven-minute track on the first CD. Speaking of the recording [Siemon] Allen points out that “it is the entropic nature of the performance, which is captured on the disk, and not the information traded at such an event...”

Other contributors to the first CD include Walker Paterson, Samkelo Matoti, Brendon Bussy and Rhett Martyn whose scatological outbursts (from the multi-media performance Aural Hygiene) evokes John Zorn’s Mikhail Zoetrope of 1974. While the second CD is a somewhat subdued compilation of Allen’s examination of the banality of social discourse. Monotonous at times it includes the provocative Sell Your Body (After Reich) a self-styled parody of Steve Reich’s It's gonna rain.

In closing it is Barry’s final words on disk one that reveal the FLAT attitude towards these cultural documents – “as much as the recording is capturing the tradition, it signifies its disintegration...” These limited edition disks are not recommended for those not attuned to subversion, banality, monotony or the erroneous manipulation of language.

Meredith Vie is a free-lance reporter writing in Durban, South Africa

unpublished review for the MAIL & GUARDIAN

Johannesburg, South Africa, 1996

|

industrial, rembrandt, johannesburg, 1995

rat in the kitchen, rembrandt, jhb, 1995

thomas barry and siemon allen

conversation 2 , rembrandt, jhb, 1995

espectically the fact..., rembrandt, jhb, 1995

exit, rembrandt, johannesburg, 1995

|

REMBRANDT GALLERY, 1995

Jeremy Wafer, Thomas Barry, Siemon Allen

EXIT, 1995 (endless)

ZULU FOR MEDICS, 1994 (90 mins)

CONVERSATION 2 , 1994 (45 mins)

ESPECIALLY THE FACT THAT I DON'T HAVE A CAR, 1994 (45 mins)

UNTITLED (INDUSTRIAL), 1995 (60 mins)

GREETINGS, 1994 (endless)

RAT IN THE KITCHEN, 1995 (45 mins) with Thomas Barry

multiple audio installations

This three person exhibition with Jeremy Wafer and Thomas Barry was organised around the time of the 1st Johannesburg Biennale. My contribution featured variations of a number of the audio installations developed out the experiments at the FLAT Gallery. These were shown earlier at the FLAT in my exhibition, Songs for Nella, and a number of other group exhibitions at that time. In both Songs for Nella and the Rembrandt show all the audio installations played simultaneosly establishing a blurred cacophony. Each individual work however could be accessed through close inspection.

Many of the pieces explored the theme of communication in the broadest sense. Some like Conversation 2, installed in an antique radiogramme, were quite literal; while others such as Industrial were somewhat oblique. Industrial is a noisy piece constructed from an initial loop of the ringing of an army field telephone which is then extended to beyond recognition. Formally the object consisted of a sheet metal box on wheels embedded with two speakers.

Exit, recorded on a 30 second endless tape, consited of a series of exit-lines one would use to extract oneself from a conversation at a social event such as an opening or party. The piece was presented on the wall with a small format cassette recorder and looped the following statements:

I'm, just going to talk to that person over there...

[pause]

I'm just going to pour myself another drink...

[pause]

I'm just going to the toilet quickly...

[pause]

In the days leading up to the audio performance Aural Hygiene (1994), Brendon Bussy brought to the FLAT a CD of Steve Reich's Early Work, which consisted of It's Gonna Rain (1965) and Come Out (1966). These recordings made a great impression on Horsburgh, Barry and myself, and its influence was immediately evident in the experimental audio work that would soon follow and subsequently become the staple of the Rembrandt Gallery exhibition. From then on, audio experiments would include not only recordings and collaged sound, but also composite overdubs, that were abstract, noisy and repetetive. I was most interested in the way that Reich manipulated 'found' sounds, and I attempted many low-tech experiments with similar techniques at the time.

In both It's Gonna Rain and Come Out, Reich created a cyclical 'wash', which he described as a kind of "controlled chaos" by superimposing repeated samples. In many of the his works, sampled words were looped until the pattern of interference rendered the meaning of the words unintelligible.

Especially the fact that I don't have a car... is one work of mine that involed this kind of manipulation. Based on a conversation with, fashion designer, Elmin Engelbrecht it began with the sampled and repetitively looped introduction of two people, Nina and Paul. The ‘introduction’ formally acted as an opening to the artwork, in the same way that two people might be introduced to each other before they commence with a conversation. Hence:

Nina/Paul/Paul/Nina,

Nina/Paul/Paul/Nina,

Nina/Paul/Paul/Nina,

Nina/Paul/Paul/Nina,[ etc…]

The introduction continues endlessly without any progression of the conversation. As the tape continues the over recording causes a breakdown in the quality of the sound, and this ‘clouds’ the two peoples’ never-ending introduction. The tension is accentuated by repetitive accompaniment on guitar, as well as tape manipulation. As the audio deteriorates, one looses any sense of the original words and the audio shifts into a ‘meditative’ drone. At times, isolated phrases, caught up in the dense recording process, come through audibly.

The ‘crescendo’ to Especially... then followed. An amalgam of all the previous recordings, this cacophonic and disturbing finale faded to a minute of silence before the final post-script, the ‘revealing stage’, took place. As this entire lengthy tape was built from a short conversation with phrases that had been fractured and multiplied, their meaning was illusive. Partially illuminated throughout the work, it was only here at the end, that the phrases would be recontexualized and restored to their original meaning.

Fused with Elmin’s voice was the melancholic music from Hitchcock’s Psycho (Herrmann). My aim was to overlay the more understated parts of this sound track to give the piece a cinematic quality, and to build tension towards an ultimate ‘resolution’. Here in the end the ‘meaning’ of Elmin’s words, as well as the title of the work are revealed:

Ja, I do. You see I… I… I understand completely what you are saying and I used to be like that when I was a little girl. I had this special place where I’d go um… this plant growing in our garden. I guess its not a plant, its more like a eh… don’t know what you call it in English. Struik [shrub.] It’s… It’s like um… a small little tree, you know, and it grows really dense and people use it for um… to put around their homes. Anyway but this place it was really dense and very green and made the most amazing tunnels inside. And it had these beautiful yellow flowers growing on it and if you crawl inside of it its like crawling into a new world. And no one knew you could actually crawl underneath this um… this plant or tree or hedge or whatever. So I could crawl in there and no one would know I was there. I was all by myself. It was like my secret place and I think that’s, that’s more or less like the place you are… It’s where I can be alone and could be myself. But now, now I’m really lucky. I can actually be by myself while I’m here, while I’m now in the room with you, while I’m in the room with a lot of people. Can be totally on my own and I’ve actually perfected it where I can even make them believe that I’m with them but I’m not - where I’m in my own world by myself; in my little space and they actually not even aware of it. I think it took me 22 years to perfect that. It works really works well for me. So whenever I need it, I can escape into it. I never even physically have to move or change… change venue. Just change the state of mind and soul. It’s really convenient. Especially the fact that I don’t have a car…

extract from the publication THE FLAT GALLERY (1993 - 1995) by Siemon Allen

published in a limited edition by FLAT International, 1999

|

internotional, flat gallery, durban, 1994

conversation, internotional, flat gallery, 1994

internotional, flat gallery, durban, 1994

|

THE FIRST INTERNOTIONAL THEATRE OF COMMUNICATION

multi-media audience participation event, flat gallery

CONVERSATION, 1994

audio performance with Elmin Engelbrecht

The philosophy that “anyone could do anything” was the guiding principal at the FLAT, and this was reflected in the audience/participation/performance, The First Internotional Theatre of Communication.

Taking place just 23 days after the historic all race elections in South Africa, it seemed appropriate and significant that this event would explore the very idea of "freedom of expression" in its most essential form.

The call for all to participate began with the printing and distribution of an open invitation by Jay Horsburgh and Thomas Barry, and embraced in a single night a broad and all encompassing range of FLAT activities. It was conceived by them to “allow anyone to do anything in the space”, and evolved with very little plan, except to bring people together with the catalysts of an open microphone, two tape recorders, some provocative wall texts and a space to interact. The goal was to allow for open expression and to ‘see what would happen’. The only condition was that no one could prevent free expression.

Not all of the events were necessarily spontaneous, and the Internotional included a number of ‘performances’ with prior preparation; including Brendon Bussy's and Tion Scholtz's

Fashion designer, Elmin Engelbrecht and I presented a ‘communication performance’ titled: Conversation. We stood silently as speakers placed above each of our heads broadcast a pre-recorded ‘banal’ conversation we had made earlier. If there was communication between us, it was only through this ‘preprogrammed’ recording and in some sense, the piece became a parody of the kind of mundane interaction some might have at a typical event such as a gallery opening.

Parts of this full recording also provided the raw material for many future audio experiments including Especially the Fact that I Don't Have a Car (mentioned above), Conversation 2, and my audio performance at the FLAT, Songs for Nella.

extract from the publication THE FLAT GALLERY (1993 - 1995) by Siemon Allen

published in a limited edition by FLAT International, 1999

|

zulu for medics, absa gallery, jhb, 1994

Extracts from ZULU FOR MEDICS.

English male..........G-14. Where do you work?

English female......You work where?

Zulu male.................Usebenza gupi?

English male...........G-15. What job or work do you do?

English female.......You work, which work?

Zulu male.................Usebenza muphi umsebenzi?

English male...........G-16. Do you still work?

English female.......You still are working?

Zulu male.................Usasebenza na?

English male...........G-17. I don’t work anymore.

English female.......I don’t still work.

Zulu male.................Ungesasebenzi.

English male.......... I don’t work.

Zulu male.................Ungesebenzi.

English male...........G-18. When did you stop working?

English female.......You stopped when to work?

Zulu male.................Uyeke nini ugusebenza?

English male...........G-42. My father is dead.

English female.......The father to me he is dead.

Zulu male.................Ubaba wami ushonele.

English male...........G-43. My mother is alive.

English female.......The mother to me she is alive.

Zulu male.................Umama wami usaphila.

English male...........G-44. My brother is sick.

English female.......The brother to me he is sick.

Zulu male.................Ubuthi wami uyagula.

English male...........G-45. My sister is healthy.

English female.......The sister to me she is healthy.

Zulu male.................Usisi wami uyaphila.

English female.......In Zulu the question form is simply a statement said with an interrogative intonation. “Na” emphasizes the question form like the Afrikaans “Né” and it is optional.

English male...........G-55. Do you smoke?

English female.......You do smoke!

Zulu male.................Uyabema na!

English male...........G-56. Do you drink?

English female.......You do drink!

Zulu male.................Uyaphuza na!

English male...........G-57. What? That is what do you drink?

English female.......You drink which alcoholic beverage, beer?

Zulu male.................Uphuza bupi utshwala na?

English male...........G-58. Do you take medicines?

English female.......Do you drink medicines?

Zulu male.................Uyayiphuza imiti na?

English male...........G-59. Do you see the witchdoctor?

English female.......You go is it so to the witchdoctor?

Zulu male.................Uyaya yini ezinyangeni zabantu?

English male...........G-61. Do you take anything from the witchdoctor?

English female.......You take is it so medicines at the witchdoctor?

Zulu male.................Uyayithata yini imiti ezinyangeni? |

ZULU FOR MEDICS, 1994

audio installation

It was my habit to visit the Point Road pawn shops in Durban to look for any kind of material that could be used in my work, and one day, about a week before the Volkskas Atelier, I came across an interesting item. It was a language tape for teaching English speaking medical students how to communicate with Zulu patients. The broad implications of such a simple object intrigued me, and when I expressed interest in buying it, the pawn shop proprietor simply gave to me what he obviously regarded as a useless item.

I was engaged at that time with a number of sound projects that dealt with issues of communication, but was also painfully conscious of my own limited knowledge of the other languages spoken in Natal, most obviously Zulu. To me the tape, in spite of its ‘well meaning’ intention, spoke not only to class distinction, but the power relations between a physician and a patient, and a white and black South African. This was revealed in the ‘probing’ authoritarian tone of the doctor as well as the personal nature of the questions.

I had used Zulu in cut-up works for the Festival of Laughter, where I took fragments of the language untranslated and experimented with random collage. With this project, however, the identity and function of the original tape was retained in the resultant sound work. The work was built on two distinctly different components that clashed and competed on one level, but combined ultimately to create what some described as a ‘disturbing’ work.

In a continuation of the experiments with my old ‘three stringed’ Spanish guitar; I amped the broken instrument by putting a microphone inside it and ‘playing’. I did not play guitar, nor did I speak Zulu, but I was intrigued by the idea of creating a soundtrack for the language tape. I played the guitar while listening to the Zulu tape and then recorded the two together. The chaotic guitar gave the language tape a mood or an edge, which seemed fitting to its subject matter.

To present the work at the Volkskas, I used an entire hi-fi system as part of the work, and this behaved like a ‘found-object’. This seemed to address the idea of the sound system as being a common household commodity, representing prestige or ownership. To me, the seriousness and complexities embodied in the tape stood in sharp contrast to the obvious commodity status of the rather ostentatious equipment.

The work was full of contradictions. There was, as with all works that ‘spoke’ through a sampled ‘black voice’, a danger of being misread. Such an appropriation might be seen as a disrespectful careless use of another. But my hope was to address the very awkwardness inherent in the bringing together of two cultures or two languages and the power relations inherent in any exchange.

It was ironic that the tape’s explicit purpose was, in the most literal sense, to promote healing. And yet it was an appropriate metaphor for the problems and pitfalls that faced the South African. Was ‘healing’ possible within the dynamics so clearly illustrated in the tape? Was the white South African ‘doctor’ the authority, the Zulu in need of ‘help’? For me that small souvenir of the best and worst of the colonial missionary spirit spoke volumes.

Many Zulu viewers were drawn to the work because of language, and as with other such works, an interaction occurred across racial lines. It was, indeed, an educational tape, and I was amused by how wooden and simple minded the non-Zulu speaker on the tape must have sounded to a Zulu listener.

from the publication THE FLAT GALLERY (1993 - 1995) by Siemon Allen

published in a limited edition by FLAT International, 1999

|

songs for nella, flat gallery, durban, 1994

songs for nella, flat gallery, durban, 1994 |

SONGS FOR NELLA, 1994

audio installation, flat gallery

The basic idea around Songs For Nella was a simple one: to create an exhibition solely around a saturated polyphonic noise. The FLAT Gallery at that time was a very chaotic environment and the insane excess of this work was perhaps a sub-conscious reflection of my own sense of sometimes living in a tempest.

For the audio installation, I set up two rooms at the FLAT and used a total of nine stereos that I had borrowed from friends. Positioned on the wall, they looked like minimal art objects before they were activated in the performance. Each stereo contained a particular audio experiment from the work I had been exploring at the FLAT. But all were played simultaneously to produce a cacophony of sound.

Unlike the original proposal for SWANS, this installation dealt with a sensory overload through the collage of multiple sound sources rather than one single sound.

from the publication THE FLAT GALLERY (1993 - 1995) by Siemon Allen

published in a limited edition by FLAT International, 1999

|

hitch-hiker poster, generator, jhb, 1996

songs for nella poster, flat gallery, 1994

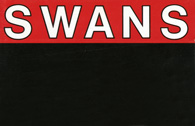

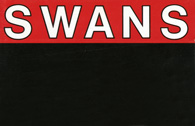

swans, flat gallery, durban, 1994

Swans was our first multi-media audience participation event at the FLAT Gallery. The premise of the show was to convert the gallery into a faux-restuarant and serve our customers, the audience. with faux-food, while assaulting them with the music of the group Swans at high volume. The performance included Ledelle Moe, Thomas Barry, Yvette De Bruin, Jay Horsburgh and Siemon Allen. An insane event!

songs for nella, flat gallery, 1994

|

EXHIBITION HISTORY

SWANS

multi-media performance with Ledelle Moe, Thomas Barry, Yvette de Bruin, Jay Horburgh and Siemon Allen

February 9, 1994

FLAT Gallery, Durban, South Africa

THE FIRST INTERNOTIONAL THEATRE OF COMMUNICATION

multi-media audience particpation event initiated by

Thomas Barry and Jay Horsburgh

Conversation (1994) with Elmin Engelbrecht

May 20, 1994

FLAT Gallery, Durban, South Africa

VOLKSKAS ATELIER

Zulu for Medics (1994)

June 1994

ABSA Gallery, Johannesburg, South Africa

NSA Gallery, Durban, South Africa

SONGS FOR NELLA

audio installation

June 10, 1994

FLAT Gallery, Durban, South Africa

AURAL HYGIENE - The Listening Chamber

multi-media audience participation event initiated by Brendon Bussy

July 8, 1994

FLAT Gallery, Durban, South Africa

QUASI-STELLAR OBJECTS

multi-media audio-visual performance with Brendon Bussy, Thomas Barry, Rhett Martyn, Willem Huysers, Jay Horsburgh and Siemon Allen

July 31, 1994

Jam & Co, Durban, South Africa

FORM OF THE FUTURE

Untitled (Industrial) (1994)

August 1994

Durban Art Gallery, Durban, South Africa

HITCH-HIKER

curated by Clive Kellner

Work (1996)

November 29, 1996 - January 1997

Generator Art Space, Johannesburg, South Africa, 1996

2ND JOHANNESBURG BIENNALE

curated by Okwui Enwezor

GRAFT curated by Colin Richards

Work (1996)

October 12, 1997 - January 18, 1998

South African National Gallery, Cape Town, South Africa

TAKING STOCK

curated by Marco Cianfanelli, Andrea Bürgener, Luan Nel

Sell Your Body (after Reich), (1997)

December 7 - 24, 1997

Johannesburg Stock Exchange, Johannesburg, South Africa

IMPORT

Markuss Wirthmann & Siemon Allen

Talk (1999)

May 20 - July 15, 1999

Goethe Institute, Washington, DC, USA

TRANSLATION/SEDUCTION/DISPLACEMENT

curated by Lauri Firstenberg & John Peffer

Zulu for Medics (1994)

February 3 - April 1, 2000

White Box, New York, NY, USA

AFTER THE DIAGRAM

curated by Lauri Firstenberg & Douglas Cooper

Marais/Brand (2001)

April 26 - June 2, 2001

White Box, New York, NY, USA

DEMOCRACY AND CHANGE

Marais/Brand (2001)

2004

KKNK, Oudtshoorn, South Africa

|